June 30, 2015

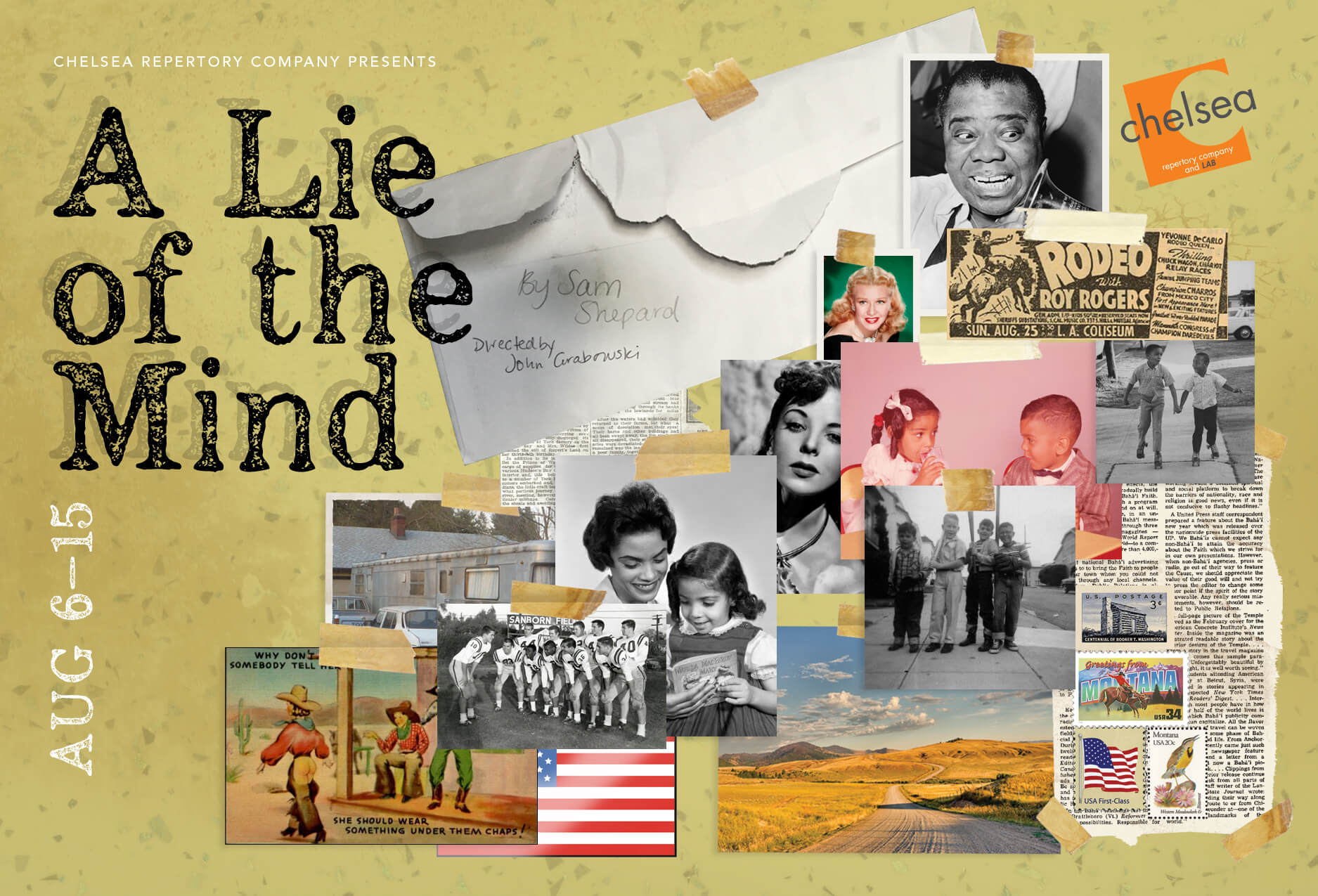

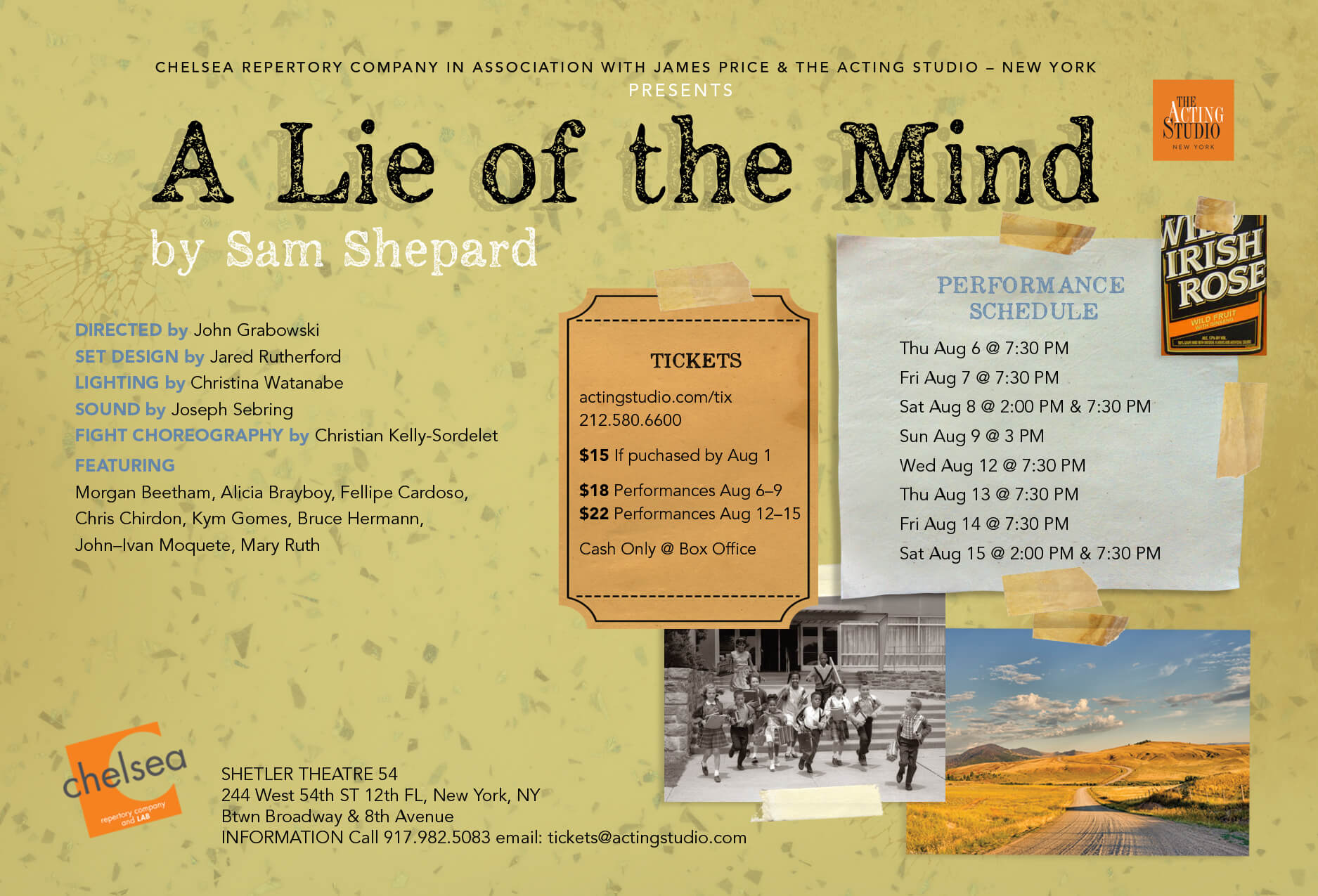

Chelsea Repertory Company presents a mainstage production of Sam Shepard's play A LIE OF THE MIND at Shetler THEATRE 54 August 6-15 for ten performances. Directed by studio associate and resident director John Grabowski, the production will feature studio actors including studio associate Bruce Hermann, Morgan Beetham and studio graduates Alicia Brayboy, Mary Ruth, Fellipe Cardoso, Kym Gomes, Chris Chirdon and John-Ivan Moquete. Set design by Jared Rutherford, lighting by Christina Watanabe, sound by Joseph Sebring and fight choreography by Christian Kelly-Sordelet

Director John Grabowski writes: When Sam Shepard was writing his series of family plays in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, - a series of plays that includes THE CURSE OF THE STARVING CLASS, BURIED CHILD, TRUE WEST, FOOL FOR LOVE and, of course, A LIE OF THE MIND which Chelsea Rep is producing in August - the theatre was in transition. The audience for traditional plays was declining and playwrights like David Mamet and Albert Innaurato were experimenting with form and writing shorter plays that took the form of extended one-acts and made a different set of demands on their audience. The interest in the shorter play has continued, and in the modern theatre, the playwright who crafts a three-act play runs the risk of never having the work performed. Shorter plays are popular with both producers and audiences in this era of short attention spans, digital technology, and increased demands on an audience’s time. However, we should remember that most realistic theatre in the late 19th century and 20th century was composed in three- and four- act format and asked its audience to sustain their attention for extended periods of time. Ibsen and Chekov wrote long plays of three and four acts, and European playwrights followed suit. Most American classic plays from the so-called golden age of theatre are three act plays: STREETCAR, and most of Williams’ other plays, Miller’s SALESMAN and other more traditional Broadway playwrights like Philip Barry, William Inge, and Edward Albee wrote mostly three act plays. Eugene O’Neill, possibly America’s greatest writer of plays, wrote many plays like THE ICEMAN COMETH and A LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT that in performance last in excess of four hours, making very real demands on an audience’s time and attention span.

Director John Grabowski writes: When Sam Shepard was writing his series of family plays in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, - a series of plays that includes THE CURSE OF THE STARVING CLASS, BURIED CHILD, TRUE WEST, FOOL FOR LOVE and, of course, A LIE OF THE MIND which Chelsea Rep is producing in August - the theatre was in transition. The audience for traditional plays was declining and playwrights like David Mamet and Albert Innaurato were experimenting with form and writing shorter plays that took the form of extended one-acts and made a different set of demands on their audience. The interest in the shorter play has continued, and in the modern theatre, the playwright who crafts a three-act play runs the risk of never having the work performed. Shorter plays are popular with both producers and audiences in this era of short attention spans, digital technology, and increased demands on an audience’s time. However, we should remember that most realistic theatre in the late 19th century and 20th century was composed in three- and four- act format and asked its audience to sustain their attention for extended periods of time. Ibsen and Chekov wrote long plays of three and four acts, and European playwrights followed suit. Most American classic plays from the so-called golden age of theatre are three act plays: STREETCAR, and most of Williams’ other plays, Miller’s SALESMAN and other more traditional Broadway playwrights like Philip Barry, William Inge, and Edward Albee wrote mostly three act plays. Eugene O’Neill, possibly America’s greatest writer of plays, wrote many plays like THE ICEMAN COMETH and A LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT that in performance last in excess of four hours, making very real demands on an audience’s time and attention span.

While the professional theatre was moving towards shorter plays in the 70s and 80s, much of the avant-garde movement was moving in the opposite direction. Performance artists began to experiment with notions of extending time and space in their work and performances could last for seven hours or more. Artists like Peter Brook in THE MAHABHARATA, Robert Wilson in EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH and Pina Bausch in 1980 blended theatre, dance and opera and let their audiences experience the works on a variety of levels. EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH lasted over four hours with no intermissions, and Wilson allowed his audience to wander in and out of the theatre as they chose. In those works, the audience who was willing to give over to the experience of those works was amply rewarded. I know because I was in the audience of all three, and they are three of the most transforming times I have spent in a theatre, each of them leaving an indelible impression.

Most of Sam Shepard’s family dramas are three-act plays and this places him, depending on your point of view, in the tradition of traditional playwrights like O’Neill, Williams, and Miller or in the tradition of the avant-garde with Brook and Wilson. The original production of A LIE OF THE MIND was over four hours in length and the 2010 revival of the play ran about three hours. I expect our production will be a little shy of three hours. It will make a demand on your time and attention, but I expect The Acting Studio’s audience as lovers of the art of acting to be willing to give their time and attention and step into the world of the play with us.

Today even Shepard disavows some of his longer plays and is mostly writing in the form of the short full-length play. However, some modern playwrights are bucking the new tradition of the short play and writing longer plays and demanding that their audience go along with them. Recent Pulitzer Prize winner Annie Baker is firmly in the camp of the long play. Her play THE FLICK is three acts and lasts over three hours. The published play script is approximately 177 pages long. Her new play at Signature Stage, JAKE is expected to last for over four hours, and in her plays there are moments that test an audience’s patience. Much of THE FLICK consists of one character training another character in the job of cleaning a movie theatre, and many of the scenes consist of them sweeping up popcorn. When it was first produced at Playwright’s Horizons, large numbers of their subscription audience left at intermission, and the artistic director took the unusual step of publishing a letter that apologized for what he saw as the production’s excesses. I recently saw that production and would agree with Charles Isherwood in The New York Times who said about the play, the characters “get to know one another, but not through the style of traditional naturalism, in scenes moving cleanly toward an emotional or dramatic turning point. Instead, they probe one another’s hearts, souls and sore spots the way we all do with our co-workers, in fits and starts, by making desultory small talk, by not letting on what’s really taking place inside, until gradually intimacy grows and friendship blooms (and perhaps withers, too). More than most playwrights working today, Ms. Baker really does have an interest in holding the proverbial Shakespearean mirror up to nature to illuminate the way we treat each other and the way we communicate — and fail to communicate.” The members of the audience who came into the theatre to see THE FLICK wanting to experience real contact and share in a rich and varied experience came away from the play rewarded, and those who were just looking for the latest distraction from their Facebook, their YouTube, and the rest of their digital world left disappointed.

I close with two quotes from a New Yorker article on Annie Baker, which I will link below. The first asks an interesting question of the modern theatregoer and the second makes an interesting point about two different ways of making theatre.

“Who goes to the theatre these days, and why? For decades now, serious stage work has been regarded tenderly as the spotted owl of American art—brilliant and nimble, breathtaking in flight, but unlikely to be found beyond a few scarce habitats. Every time we watch a trite blockbuster, fall asleep in front of bad TV, or click through to a YouTube video of yawning pandas, it’s said, our capacity for theatrical attention dies a little more. And yet, for all that, the theatre has proved strangely resilient, selling (even selling out) cascades of seats and claiming more college degrees than film and clinical psychology combined. Something is going right. Perhaps the question isn’t why some give up on the form but why others keep falling in love. What can the theatre do that books and screens can’t?”

“Artists are pulled these days between two warring camps. On one side lie what might be called the Experientialists: those who believe that the point of art is to have the audience undergo a particular experience in time—and that the audience’s responsibility is to submit as fully as possible. (Think of Antonioni, who kept his cameras open to the unexpected.) On the other are the Arrangers: people who think that the role of art is to order, burnish, perform, and engage desire. (Think of Hitchcock.) Experientialism honors the artist’s sensibility: À LA RECHERCHE DU TEMPS PERDU may be dilated and slow, but it’s only by giving in to the author’s method that we can experience its genius. Arranging, by contrast, defers to the audience: what makes THE GREAT GATSBY better than any of a hundred novels with comparable cultural freight is that it’s economically written and smartly plotted, seducing us without special conditions. Diehard Experientialists accuse Arrangers of pandering with “easy art” and cliché. Arrangers mock Experientialists for self-indulgence, tedious abstruseness, and bad faith. (The lousy Experientialist claims that his disjointed, boring novel is supposed to be that way.) The ablest artists are those who inhabit a middle landscape, mastering the art of special attention while meeting the challenges of effortless appeal.”

TICKETS ONLINE: www.actingstudio.com

BY PHONE: 917.982.5083

ADVANCE SALE: $15. (tickets purchased before 1-AUG)

AT THE BOX OFFICE: Cash Only

$18- Performances Aug 6-9

$22- Performances Aug 12-15

244 West 54th ST 12th FL, New York, NY

Btwn Broadway & 8th AV

INFORMATION: Call 212.580.6600 or Email: tickets@actingstudio.com